Culture, history and people: The key to understanding drinks better, with Dr Anna Sulan Masing

Seeking to articulate her indigenous Iban identity, writer, poet and academic Dr Anna Sulan Masing discovered the importance of understanding the value systems behind our food and drinks

Memories of childhood are always viewed through a soft lens; timelines are out of sync, everything is bigger, and possibly brighter. In adulthood, flavours are etched into our minds, and scents waft past and drag us back to our younger selves.

For me, as someone who has multiple places, spaces and cultures that I call home; who has snatches of memories that consist of tropical heat on the skin and salt from sweat on my lip, as well as whip of cold from windy New Zealand winters, the idea of childhood is not one that is static or even stable.

My indigenous identity, being Iban – a community in Sarawak, a state of Malaysia on the island of Borneo – was always something that was based on feelings and memory. It felt tangible but also hard to explain. It was something that gave me a base, but I couldn’t find a way to articulate it in the Western world that I lived in, and my work has been searching for a way to give these memories words.

In the colonial eye

South East Asia was a jewel in the European colonial eye. Banda island in the Indonesian archipelago, known by Europe as the ‘Spice Islands’, were deeply sought after, fought over, and exploited by various European powers; if you could paint history, the seas around these islands would be painted in blood.

The Dutch and the British carved up seas and lands of Malaya, Singapore and Indonesia, controlling goods – spices, rubber, coffee. Spain laid claim to the Philippines and France further north. Sarawak was slightly unusual – it was ruled, or owned, by one British family from 1841 to 1946.

My indigenous identity, being Iban… was always something that was based on feelings and memory. It felt tangible but also hard to explain.

But before this colonial era, South East Asia was part of a dynamic trading system across the Indian Ocean and further east. Pepper from India came through Sumatra to go to China; indigenous peoples like the Iban came to the coast to trade their jungle-foraged produce, which found its way much further afield; and nutmeg went west to eventually land in the laps of Europeans. The Western empires sought to dominate, monopolise and control this trading – to own the system, the people, and the lands, causing unfathomable brutalities.

History is still with us

These systems are still in place today. We see it in the inequality within the trade system, where global south farmers are paid so little. They are vulnerable to a global commodities market that doesn’t take into account the cost of farming, and they have to be reliant on multiple middlemen to get their goods to the wider world, each needing their cut of the profits.

There was a shifting idea of origin, and a strong sense of self, and community identity that I wanted to be a part of again.

We also see it in the way we, the global north, disregards labour – do you know who grows the black pepper that sits on your table? We see these systems when we look at who now has power, wealth and an equity in the way the future will look.

But this was all information I learnt in my quest to understand home. I wanted to delve back into the stories of my childhood, the ones my Iban grandmother told me. There was a shifting idea of origin, and a strong sense of self, and community identity that I wanted to be a part of again.

Identity, space and change

My PhD asked how identity changes when space and location changes, and looked at the performance and storytelling practices of Iban woman. What I found was a deep connection to the farming cycle, where rice was the crucial element of life.

My father wrote in a paper about rice cultivation, “There is a value system based on [rice] padi culture. This value system is not kept because padi is an essential food crop. But, more often than not, it is kept based on the belief that padi has a spirit which must be pacified through cultivation.” (Padi is a Malay word and where ‘paddy’ originates from.)

Food and drink are tools of storytelling, and rice is central to the idea of home, and farming it the thread of the Iban stories.

The Iban farm traditionally uses the swidden system, where they clear land for planting, then give that land a rest for a season or more (a system that colonial powers tried to eradicate). This meant that they moved through space to find new lands to farm.

I don’t want to romanticise the Iban, this caused wars as they came across other tribes. But what it did do was create a sense of home through movement, belonging was something that could occupy multiple spaces. Food and drink are tools of storytelling, and rice is central to the idea of home, and farming it the thread of the Iban stories. When the Iban migrate, they take their stories – and rice – with them.

The stories we tell

The harvest festival, Gawai, is the main celebration of the year. The myths and stories of Gawai invite gods to come and join the feasts, where they are sent rice and tuak. During Gawai three different types of rice, eggs and tuak are left in offering.

Tuak is an alcoholic rice beverage that is brewed to a wine-like ABV. It is part of celebrations, harvest, and the very essence of being Iban. Families have their own recipes and everyone has their favourite brewer. Tuak is so obvious in its relationship to farming, you can still smell and taste the rice, that scent of fermented grain is clear. It is no longer rice, but it is of rice. Agriculture is what makes Iban society, what builds the identity, what physically brings everyone together as a community.

Understanding how culture, history and people are all equal parts of a story allows me to seek deeper understandings of drinks.

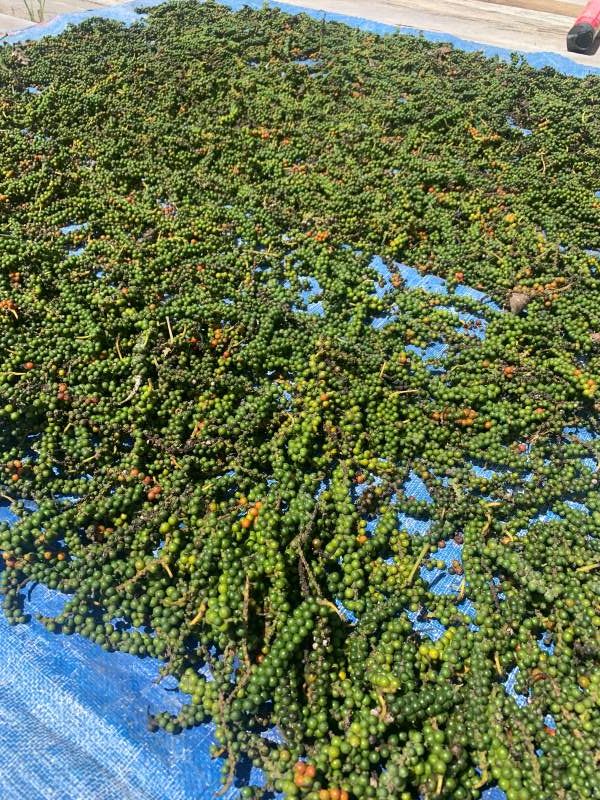

Looking into this very personal research, and this very specific small community on the island of Borneo, made me see wider connections. Iban are migrating to cities, to move away from farming. Farming is still happening but is part of a larger agricultural system – such as pepper being farmed as a cash crop deep in the jungle, to be exported far and wide.

Pepper was introduced in the late 1800s, with Chinese migrants the first to cultivate the plant, before indigenous communities farmed it as a cash crop. Delving into the histories of the Iban it was impossible not to see the colonial history of South East Asia: it was the context of how farming changed, why cash crops became important.

A deeper understanding

Alcohol, like spices, can travel easily and far. It too is like spices in that we can forget who farmed it, harvested it, processed it. With spice the distance can allow us to forget the systems it is a part of, the people who cared for its early forms – berries, bark, seeds. And alcohol, before it is turned to liquid, is also cared for at every step of the way. Tuak is immediate in its connection with people, place and plant, but how do we think of other drinks?

Spice is what took Europe to South East Asia, colonialism is what made me, a mixed-race woman, possible; rice is what grounds me in my sense of home and belonging; and understanding how culture, history and people are all equal parts of a story allows me to seek deeper understandings of drinks.

I write about these histories to seek a more equitable future for the planet, a more sustainable one. I want to not see my childhood as a nostalgic memory but see it as a part of those spaces of labour where people grow wonderful produce to be honoured and respected.

[Lead image credit: Whetstone Radio Collection]