Bartending as a career: Asia

As Asia continues to grow in visibility on the global bar stage, we take a look at how the profession has been perceived in the past – and ask how this could be changing. From Tokyo to Goa, six bartenders on the ground tell their stories

Biznu Saru has his father to thank for introducing him to the world of bartending. “He used to serve in the Indian army and when he would get back from Rajasthan, he would mix rum punch and Cuba Libres. I heard he was a bartender in the mess for his senior officers and that is how I got to know about bartending.” Now, Saru teaches scores of young and hopeful bartenders-in-training through his Nepalese school Cocktail Workshop to build a solid foundation of local talent for the future of a relatively young cocktail industry in south Asia.

When it comes to discussing the profession of bartending in the world’s largest continent, Asia, perceptions, misconceptions, and preconceptions are nuanced depending on the cultures in which they are happening. In some, a negative view of alcohol consumption is naturally associated; in others, an association with sex work can be a barrier, class systems can impact the desire to work in a service role, and the eschewing of more ‘accepted’ careers (law, medicine) a disappointment.

However, in 2023, Asia’s bar industry is buzzing, and more and more of its bartenders are being rightly recognised on the industry’s global stage. Guest shifts are changing too, from the pre-Covid influx of teams from the West, to a more internal exchange of knowledge with bars from inside the continent – and brands are putting their money where their mouths are too by investing in education. India is reported as being one of the fastest growing alcoholic beverage markets globally, Singapore saw the arrival of BCB in 2022, Vietnam hosted its first whisky festival (and associated bartender competition), and Campari Academy itself just launched in Asia this year (2023) – to name a few of the continent’s recent big moves.

And while this feature is not exhaustive when it comes to the many different cultures and countries that live under the catchall term ‘Asia’, the interviewees represent a cross-section of approaches to the bartending profession, to encourage a conversation around the core question: ‘How do you build a career as a bartender in Asia?’

In the beginning

For a lot of today’s best-known bartenders in Asia, their origin stories of working in a profession perhaps not much spoken about are, unsurprisingly, tales of the unexpected. Soran Nomura picked up his trade after leaving his studies at art school in London. “One of my friends was working for Cantaloupe Group, so I got my first job at the Big Chill bar in east London and as soon as I started, I fell in love.”

It marked the beginning of a seven-year stint in the capital before his visa ran out and he found himself moving home to Japan where he discovered finding a community of like-minded people to be rather difficult. “At the time there were only a few young bartenders around and I was trying to meet up with them, but it was hard to find those people… I was struggling to meet people with good skills, same-thinking bartender people.” Now, Nomura runs multiple spaces in Tokyo, from his retail venture Nomura Shoten to new bar and studio Quarter Room.

“I was struggling to meet people with good skills, same-thinking bartender people.”

Soran Nomura, Nomura Shoten

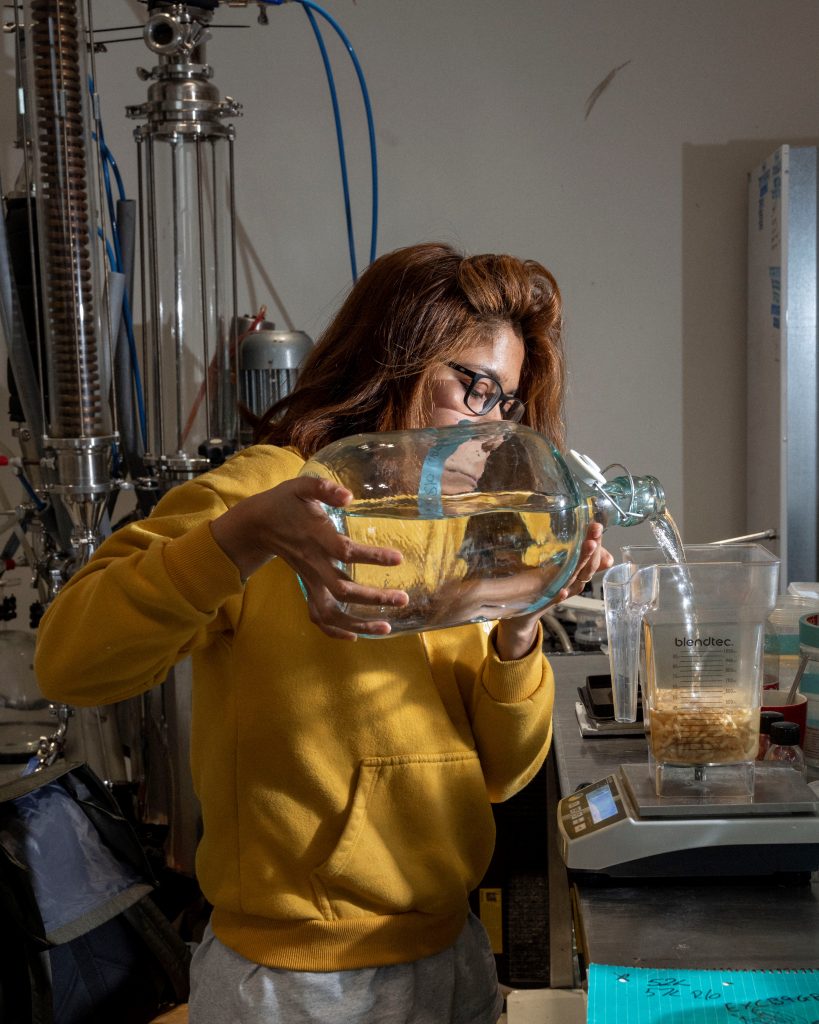

Over in Singapore and Sasha Wijidessa (who is soon to open Fura with co-founder chef Christina Rasmussen) found herself choosing between bartending and the pharmaceutical industry after taking it up to make some extra cash while she was studying. “Soon I realised I really loved and enjoyed every part of it, being in a creative space, making drinks, the creative process, being part of a team… After my graduation, I was kind of at a crossroads: either further my studies or continue bartending full-time. But I’ve never been so passionate and devoted to anything else I’ve ever done so it seemed only fair to myself to choose to do something that I love – so I chose bartending.”

For India’s Arijit Bose, however, watching his father (a good cook) run a small lodging meant that for him, hospitality was on the cards from the start. After deciding to study hotel management, he was sure it would be in the guise of a chef – until he experienced his first bar. “When I saw my first bar, my life kind of changed. I enjoyed the history, the piano, the lady singing: it was the first time I realised I wanted to be in the bar.” Since then, he’s travelled the world as a brand ambassador, sales and marketing man, bartender and bar owner – and now he runs consultancy agency, Countertop, which has a vision of planting India more firmly on the global F&B stage. (He was also instrumental in Goa’s bartending scene having opened Bar Tesouro, which he recently left.)

Living proof

While these now influential individuals have gone on to be recognisable names in their fields, the road hasn’t been an easy one and stigmas surrounding bartending (while changing) do exist. Over in Malaysia, renowned bar owner and tender Karl Too, who currently runs Happy Stan in Kuala Lumpur, tells me: “In Malaysia, historically, the perception of being a bartender was often viewed negatively due to the association of alcohol consumption, with negative behaviours such as drunkenness and promiscuity. There’s also a cultural stigma against alcohol consumption in some parts of Malaysian society, particularly among the Muslim population who make up the majority of the country’s population.”

“In Malaysia, historically, the perception of being a bartender was often viewed negatively due to the association… with negative behaviours such as drunkenness and promiscuity.”

Karl Too, Happy Stan

This attitude towards drinking alcohol is something Saru has experienced too, not just with his own profession but with his work to build others’. “When I say I’m a bartender, peoples’ perception of me is, ‘Oh, he knows how to drink’,” he explains. “When I started my academy in 2016, there were days when a student would come in and his or her parents would say ‘They will be a drunkard, they will start drinking alcohol’.”

Interestingly, Nomura’s experience in Shinjuku, Toyko, is an inverted one of Saru’s and Too’s. “People of my parents’ age drink quite a lot – they used to come every Saturday to my house and on Sunday mornings people would be lying down in my living room… People my age are scared to get drunk – they’d rather drink non-alcoholic or low-alcohol drinks.”

Hopes and dreams

While some may cite the attitude to alcohol as a barrier, Wijidessa isn’t sure if it’s really the focus: “I think there is less of a taboo with alcohol in most parts of Asia than we think,” she says. “Although I do think for the longest time bartending has not been viewed as a ‘respectable career’ which I believe is tied a lot to traditional views of what a career should be.” Indeed, the plan for Wijidessa originally was to do dentistry after she graduated from pharma science. “To say that my parents were disappointed is quite the understatement. But they have since come around and are super supportive of my career.”

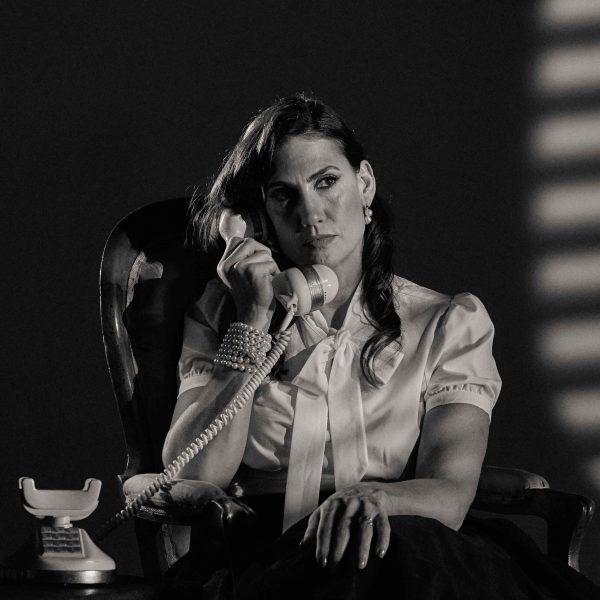

One of the industry’s most recognisable women working behind the bar, Bannie Kang of Singapore’s Side Door, fell into the world of bartending after moving to the country to improve her English before finding herself behind the bar. She has experienced first-hand the underlying negative perceptions surrounding her profession of choice. “My family are very traditional Korean – my dad works in the office and my mum is a housewife –which makes them not supportive of my job due to lack of understanding,” she tells me.

Class systems in India play a role too, Bose tells me of the perception and sometimes barriers to getting into the industry. “If you come from an educated background where your parents are scholars you would automatically target engineering, banking, investment, but you’re not moving to F&B,” he explains while also citing the taboos around talking about money and the difficulties that arise with managing a team when a nuanced and visible class system are in place. More specific to Goa, however, and with drinking not looked at as negatively – and with its Portuguese past – the ability to communicate drinks is better, he says, than a lot of the rest of the country, making it a hive for budding bartenders.

All change?

But if Asia’s bartending scene is growing, does that mean perceptions are changing? And if not, how can they? Too believes Malaysia is definitely seeing a shift – especially in urban areas – for a number of reasons: “This shift in perception can be attributed to several factors, such as the rise of international cocktail competitions, the opening of high-end bars and restaurants that offer elaborate cocktail menus, and the increasing demand for quality cocktails and mixology services at events and parties.”

“The key point will be how we could work more on education and the image of these jobs, as it will let others have a better understanding of our industry collectively contributing back to society.”

Bannie Kang, Side Door

Kang sees the acceptance of the bartending community outside of the industry as having a bigger impact on Asian society more widely. “Our community is very important not only for me in my role in the bar industry but in other industries too. We have such potential to make an impact on our future. The key point will be how we could work more on education and the image of these jobs, as it will let others have a better understanding of our industry collectively contributing back to society.”

Wijidessa echoes her sentiment: “I don’t think it’s the [change of] perception of bartending that will make our community stronger, I think it’s more the lack of understanding of what we do and more importantly why we do what we do.”

Back to Too and it will be the right messaging and promotion of the industry that will make a difference, targeting specific groups of people, such as those who might be sceptical about career growth and financial reward. A focus on its creative and artistic aspects are important too. “Bartending can be an attractive career option for Malaysians who are passionate about hospitality and mixology. I have been coaching and mentoring a particular group of talented individuals which I believe they have potential to influence and further improve the quality of local F&B landscape. This [has been] a lonely uphill battle since 2019.”

Local talent

This leads to a delicate aspect of the DNA of the Asian bar scene: the relationship between ex-pats and local talent. While international talent has certainly played a role in its recent history, the focus on local talent is also something that the industry is keen to see more of. “I think more and more we’re bridging the gap,” says Wijidessa of the balance between the two. “When I first started bartending nine years ago, the majority of the bars had an ex-pat running the program, but now we’re seeing a lot more locals being empowered.”

“When I first started bartending nine years ago, the majority of the bars had an ex-pat running the program, but now we’re seeing a lot more locals being empowered.”

Sasha Wijidessa, Fura

Bose is keen to credit ex-pats from the likes of Australia and Italy for helping him learn how to manage a team and as a way of setting a standard for the first big generation of local talent. “I learned how to manage a team not from Indian predecessors but from people outside. If you look at the right people, they will build up a generation and now the second generation is where the guys they trained are taking up those positions. If ex pats hadn’t come into our industry, it would be very different.”

Too is keen to impress that while ex-pats in Malaysia have played an important role in its development, a diverse and inclusive bar culture should reflect the local community and its values as much as possible: “This can involve actively promoting local talent and ingredients, as well as embracing new ideas and perspectives from around the world.”

For Saru, his work with locals from less wealthy families who may not be able to invest in a career is his way of encouraging more local talent into the industry through scholarships.

Building the future

Retaining talent is something that will be important to keeping local bartenders in Asia too and strengthening the message that bartending is a noble and sought-after profession. The methods suggested for doing so are not dissimilar to those cited across the industry globally.

“If we want what we do to be a lifelong career, then we need to create a working environment that can give you balance and a career that can blend with all the other aspect of your life,” says Wijidessa. “Sure my body in my twenties can handle a 90-hour work week, but what about when I’m 30? Or 40? Or 50? If I can’t say that I can do what I do now when I’m 50, then it’s a career that is not sustainable. Now a lot of my work goals are tied with creating a balance and blend of my personal and work life.” Nomura is also working hard to build a business that promotes this way of working, instilling eight-hour shifts into his numerous businesses to help with staff balance.

“I hope it comes to that level where there is a lot more talent than places opening, and the talent running places too.”

Arijit Bose, Countertop

Bose meanwhile is busy growing what he calls an ‘ecosystem’ in India to grow the market: “I’m not tied up with just bartenders but artistic people from other vocations like a video game developer, and architect a business research group, to see how we can take whatever learnings and use them.” What are his hopes for the future of his bar scene? “I hope people find this industry fun and that they don’t find serving other people degrading… I hope it comes to that level where there is a lot more talent than places opening, and the talent running places too.”

For Kang, a continued willingness to learn will stand any young bartender in Asia in good stead: “Stay connected, stay humble, stay hungry for knowledge.”