Tan Ding Jie is on a mission to answer the question: Why ferment?

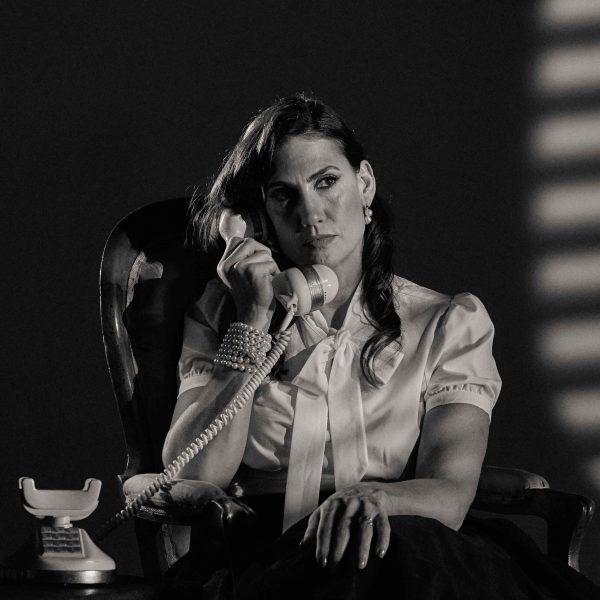

We sit down with the Singapore-based scientist Tan Ding Jie, and founder of bio-tech company Starter Culture, to chat how Asia’s ferments have travelled around the world, how bar professionals can unlock new flavours, and how he’s experimenting with this age-old technique

No place can be compared to Asia when it comes to fermenting traditions. A huge amount of the most common and beloved foods originate from here, some of which might come as a surprise. Ketchup (or in its original Chinese, kêtsiap), for example, was imported to the West during the 17th century by British and Dutch merchants. Bread and beer also likely came out of ancient Mesopotamia, says Tan Ding Jie, who is building a name for himself in his hometown as the guy to speak to when talking all things fermentation.

“Everyone is excited to have new flavours to play with, like an artist with new colours of paint on their palette.”

Though working closely with several bars and restaurants (Michelin-starred Labyrinth and Gibson cocktail bar in Singapore are among his most praised collaborations), Tan is not part of the hospitality business per se: he’s a scientist, and thanks to his research on fermentation, slowly becoming an integral part of the local scene. “It’s just like being a bartender or a chef, except that we can’t drink what we make,” Jie jokes of his role, which involves experimentation in the lab, as well as reading up on techniques and protocols in the library.

Fermentation is a method that, while being commonplace in food and drink production for centuries, continues to fascinate bartenders who are working in the advent of ultra-modern mixology and working with this ancient method in order to transform existing flavours or create new ones to use in cocktails. “[It] allows bartenders and chefs to create something truly novel, unique, and expressive.”

Going global

Each region in the world has local ferments which play an essential role in the local food or drink culture: Russian kvass, Polynesian poi, East African injera, to name a few. In the last decade, Asian fermentations are spreading around the world much more than before: “Asian fermentation has traditionally not been studied or exported outside of the Asian diaspora,” Tan admits. “I think that everyone is just excited to have new flavours and ingredients to play with, much like an artist with new colours of paint on their palette.”

While fermentation has for a long time been a pivotal element in Asian food and drink culture, in more modern times, it is becoming even more popular outside of the continent too with hospitality professionals. Tan Ding Jie reasons that, “with Asian culture being in the middle of a revival in interest, culinary arts in particular over the past few decades ,chefs and bartenders are looking into it more and more.”

“Use what’s available in the native area, ferment originally, and follow the seasons.”

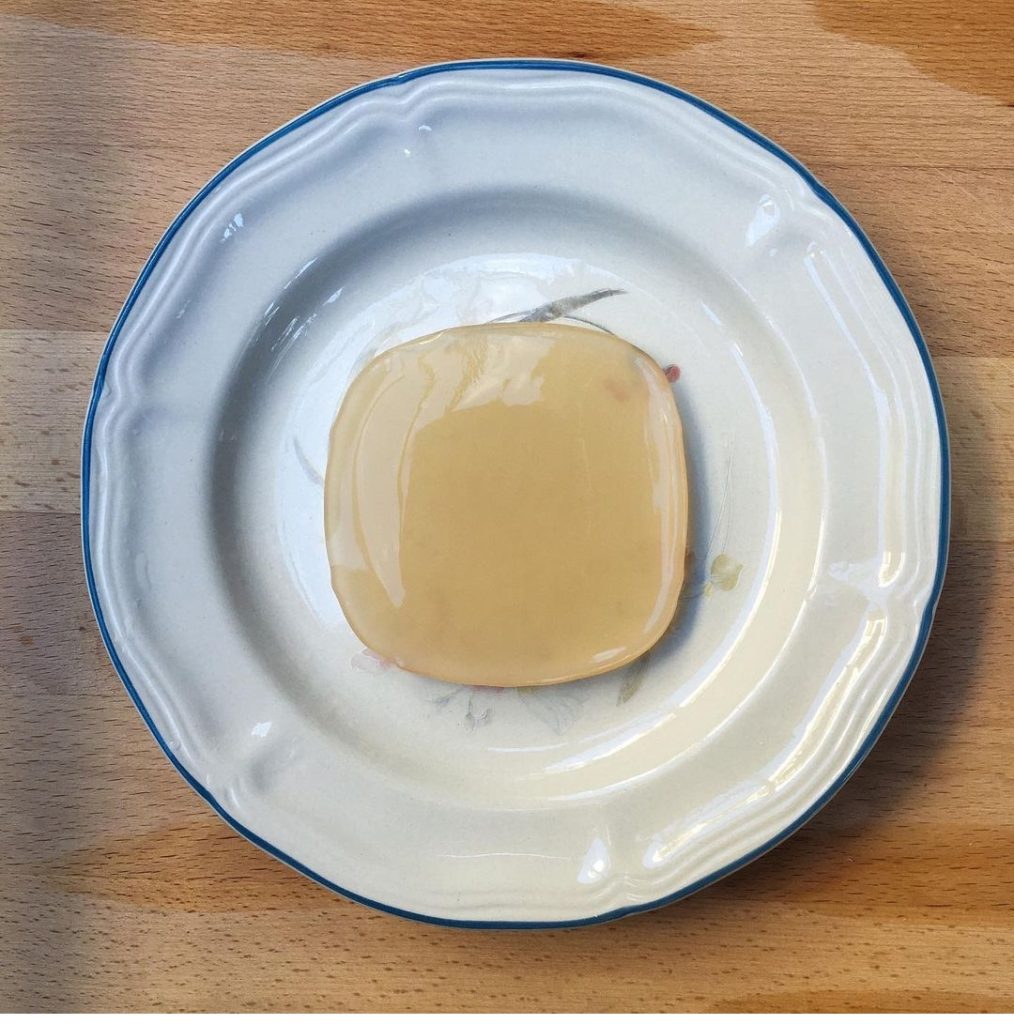

Kombucha is just one of the many ferments originating from Asia, and now readily found around the world in varying degrees. Other popular Asian ferments are kimchi and cincalok: “They are actually similar in their processes,” Tan explains, as “both are fermented with lactic acid bacteria and hence have similar acidities.” Tempeh, instead, is traditionally made out of soy beans, Jie explains, fermented by a filamentous fungus, which produces a white mycelium that wraps the product in a cake.

Singapore’s signature

Tan advocates for his native Singapore to develop and push its own style of fermentation, for the nations’ produce to shine on the international stage. Quite like the country’s essence, he describes the Singaporean fermentation style as “modern and technology-driven, coupling microbial strains from all around the world with equipment like water baths, incubators, and rotary evaporators; while still grounded in technique, heritage, and locality”.

Local fermented traditions are a very much appreciated treat: cai po (fermented radish originally from China) and nata de coco (fermented coconut water) are ubiquitous in local dishes. But Singapore being geographically surrounded by other nations with extremely rich food and beverage backgrounds has led the country to being what Tan describes as a mishmash of recipes and culinary heritage, making it harder to establish an identity on an international stage.

“You need to really understand the product you have in mind, whether it is a dish or a cocktail. How can fermentation help to achieve what you want?”

The keys to develop a country’s own style of fermentation are simple however, according to Tan: “Use what’s available in the native area, ferment originally, and follow the seasons. Singapore has conventionally been thought to have limited resources, which has forced us to think outside the box and find creative solutions. Sometimes limitations and restrictions can spur creativity, if you know your resources, waste less, and work with what you have.”

The main goal

Boosted by this philosophy, Tan Ding Jie started Starter Culture, one of his main projects. It’s a Singapore-based food biotechnology company with a focus on fermentation, aiming to bring local produce and tradition to the attention of the general public. It’s main goal? To “democratise fermentation and food science expertise”. Tan does this by holding community workshops, hosting classes at hawker centres (the iconic Singaporean food malls) and teaching how to make kimchi or kombucha. “The whole idea revolves on making it easy: most importantly, we share how to make produce that is available… not impossible creations.” It stated off attracting home cooks – now the team is seeing more chefs and bartenders attending their workshops.

Bartenders are very susceptible to the curiosity fermentations brings with it, given the aforementioned ability it has to provide drinkers (and bar professionals) with new flavour experiences But often, they neglect the fundamental question of first principles: why even ferment?

“Not all ingredients or flavours benefit or even hold up over fermentation,” Tan explains. “As a result, the product may be worse-off by the process. First, you need to really understand the product you have in mind, whether it is a dish or a cocktail. How can fermentation help to achieve what you want?” If it makes sense, he goes on to explain, then go on to analise the sugary part, which is pivotal (otherwise you would pickle or cure). Then, you must comprehend what the connection is between sugar and the final product: “If you’re looking for something alcoholic, then you need yeast. If it’s vinegar, then you need bacteria. You must know what you want, and go step-by-step, instead of just shooting in the dark.” It’s about understanding the whys more than the hows.

In detail

A key consideration though to bear in mind when working with fermentation has to be hygiene: molds can in fact be dangerous if poorly handled, as mycotoxins are not destroyed by heat, explains Tan. Depending on the mold, the toxic ones can cause food poisoning. But among the challenges of working with fermentation such as this one, achievement lies in the benefits: especially in discovering the variety of flavours it can create.

Tan highlights fermented durian as one of the most surprising experiments he ever conducted: “It is also known as tempoyak – tastes like onion chutney with blue cheese! But my first ever ferment, I will never forget: it was sauerkraut, so fermented cabbage with 3% salt solution. After two or three weeks, I put It in a jar and it started releasing this fresh blackcurrant aroma, that got me to understand how wide the opportunity of use was.”

Being an incredibly vast topic, fermentation can be implemented in many different ways behind the bar, but can also have the potential to make an impact on the bigger picture: that’s the next step in Tan’s career. After four years in consulting, last year he joined a start-up incubator, and co-founded Prefer, a company that is turning a very familiar product on its head: “We make coffee without using coffee beans. We implement food waste, working with tofu manufacturers or beer brewers; we collect their waste and ferment them recreating coffee notes. We are already experimenting with different varieties of it, working on extracting more fruity notes.” Just 15 grams of food waste are enough for one espresso, he says: that’s the magic of fermentation.