Flavour of: Seoul – Sool

A category in its own right, sool encompasses the vast sea of Korean fermented and distilled drinks. From makgeolli to bokbunja-ju, we take a dip into the flavourful world of sool

Korean drinking tradition is dominated by a term that comprises the impressively wide variety of local products, whether fermented or distilled: sool. Etymologically, it derives from the terms ‘soo’ (‘water’) and ‘bool’ (‘fire’), referring to how traditional Korean generations would describe the effect of fermentation.

Sool is based on a very simple mix of water, rice and ‘nuruk’; the latter being the most used fermentation starter in Korea, first implemented in the third century. It’s a disc made of moistened wheat, rice, or barley, dried in a heated room (‘odol’) until it starts to generate mold. Recipes used to make sool today have little to no differences from the ones implemented 1,700 years ago, showcasing how deeply sool consumption is rooted in the country’s history and tradition.

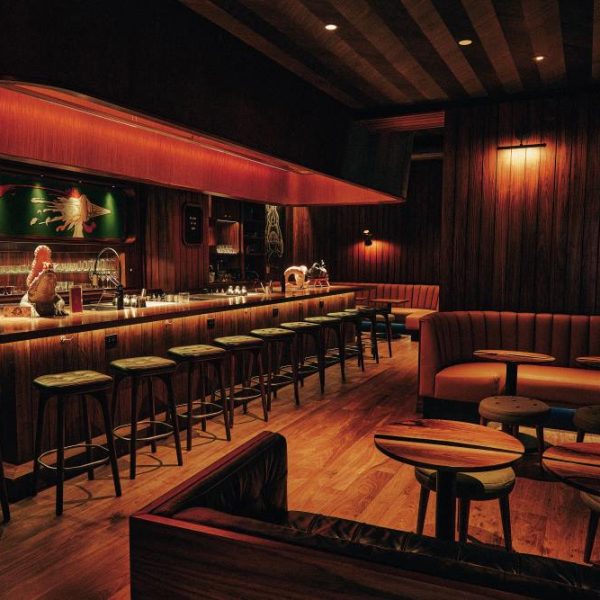

“Sool have one for any style and any personality,” comments sool sommelier Dustin Wessa, owner of Namsan Sool Club in Seoul. “Once you try it, the chase for the perfect one begins.” A staple in Korean culture, sool plays a key role in the local social fabric, being a pivotal element in celebratory gatherings (such as public holidays, commemorations, ceremonies), as well as in daily life. Drinking is recognised as an important social lubricant, and sharing drinks with colleagues and employers is a well-established habit to strengthen personal bonds.

Hundreds of products are available under the sool category: here are a selection for you to begin with to sample some authentic Korean liquid history.

Makgeolli

One of the oldest alcoholic beverages known to be created in Korea, makgeolli is named after the combination of the Korean words ‘mak’ (‘just now’) and ‘geolleun’ (‘filtered’). Despite being seen as a cheap product for decades, makgeolli has recently been on the rise both in quality and availability, thanks to younger generations of brewers, and it is today one of the most loved and consumed sools.

Rice, yeast and water are left to ferment in clay pots, for a variable amount of time (usually around three weeks); this creates ‘won-ju’, a rice-based generic beverage. Within this, the rice sediment (‘tak-ju’) settles, and a lighter, clearer layer forms on top of it: it’s the ‘cheong-ju’, which is also sometimes distilled to make ‘soju’ (see below). When tak-ju is diluted, it yields the makgeolli.

Given its low-class origins, Wessa explains how a lot of the farm-working class were paid in makgeolli from the aristocracy. Depending on the grain it is made of and the technique, makgeolli can express various flavour notes, all of them gathering very interesting nuances: rich and creamy, sour or sweeter, plain or carbonated.

Cheong-ju

Following the aforementioned process, cheong-ju can be produced too: it’s a refined rice wine, often made with the addition of other grains (barley in particular) to add depth and flavour, and spices such as cinnamon or ginger.

After the fermentation, the whole product is filtered and smoothed out: “Unlike the murky makgeolli, cheong-ju goes through an additional filtering process, resulting in a cleaner taste,” adds Pat Park, owner and bartender at Pine&Co in Seoul. “As I entered my thirties, I found myself seeking out cheong-ju more often due to its crisp flavor.”

Once a treat reserved for royal bloodlines, it is today largely consumed during meals, and works wonders as a cooking ingredient in marinades or condiments. It tends to be more dynamic than the other products, with a higher abv and a more defined character, and some varieties are very viscous and juicy. “Cheong-ju pairs exceptionally well with seafood, so I highly recommend trying it with Korean-style sashimi,” suggests Park.

Soju

The Korean national beverage, and the best-selling spirit in the world (a soju brand borders 65 million cases sold per year), soju is a distilled liqueur, ranging from 20-25% abv, mostly consumed paired with food.

It was introduced by the Mongolians during the 13th century: “They had arak, and taught Koreans how to make it,” recounts Hwi Yun, bar manager at Bar Cham in Seoul. Originally made from fermented rice, it witnessed dramatic change in the midst of the 20th century: as rice was too precious of a resource to feed the population during the Korean War, soju began being distilled from other grains such as wheat, potato and barley.

Literally meaning ‘alcohol with fire’, due to its link with distillation, soju can be enjoyed in two ways: “Traditional soju is distilled using clay pot stills,” Yun explains. “But most Koreans drink diluted soju, the so-called green bottle soju. It is a base of neutral spirit with added sweetener, and can originate from potato, tapioca and so on, distilled up to 95% abv. Soju companies buy the spirit from designated neutral spirit companies and dilute it down by 16-21%, depending on their target. We call these alcohols soju but ingredient, method and taste are completely different from one another.”

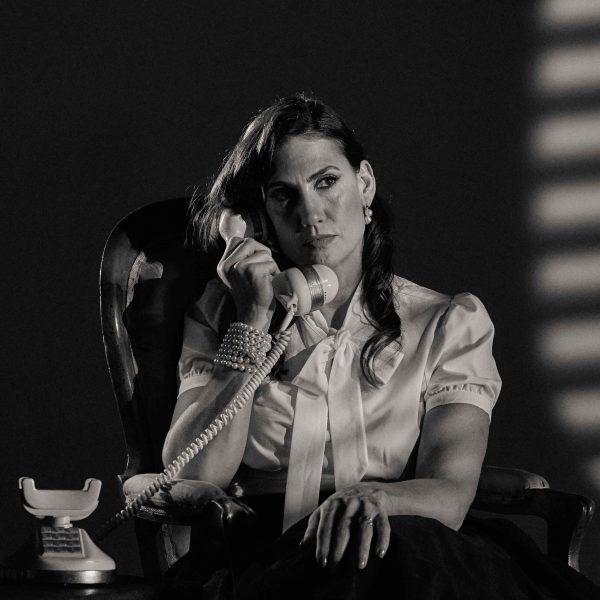

Julia Mellor, founder of The Sool Company, expands on the two categories of the spirit: table-strength soju and spirit-strength soju. “Table strength is anything below 25% abv, and is often designed to be enjoyed with food. Whereas spirit strength soju is complex and distinct in flavour, with a diversity of aroma profiles. The concept of high-proof soju is still finding its feet in Korea, and we are working to promote it internationally to discover its yet-unlocked potential in the cocktail market.”

Soju’s aromatic sip is also the protagonist of one of the most beloved drinks in the country: ‘somac’, also known as a soju-bomb, in which a shot of the spirit is sunk in a local lager.

Bokbunja-ju

‘Rubus coreanus’ is the scientific name for the bokbunja, a Korean native blackberry, known to the indigenous population for at least one millennium, and heralded for its health properties (high in vitamins and calcium, and very commonly consumed due to its supposed aphrodisiac qualities).

It was traditionally infused in a neutral spirit (often soju) and combined with sugar, to create a liqueur called bokbunja-ju; recent versions use the same name for an actual fruit wine, obtained by fermenting the berry with yeast. Flavour notes vary accordingly: “It is not as widely consumed as other sool giants such as soju or makgeolli,” Mellor comments, “but it is often an alternative at the dinner table for those who don’t like either.” The flavour profile of bokbunja, she says, is often sweet, earthy, with a heavy body, and has an abv usually between 14% and 19%. It also tends to be less acidic and sweeter compared to the varieties commonly found elsewhere, yelding a rounder product.

Alongside the better known sools Korea is fond of, you could find a series of lesser-known alternatives that will conquer your palate and interest nonetheless.

Gwaha-ju

Literally translated as ‘summer passing alcohol’, gwaha-ju is Korea’s answer to port wine, according to Mellor. “As sool brewing was traditionally something done on a smaller scale in the home, recipes and styles were often developed to reflect the seasons. In the summer, Korea is hot and humid, which does not lend to optimal brewing conditions. As such it was a time for fermenting nuruk, and also the compounded alcohol gwaha-ju: it is made by adding high proof soju to the mash early in fermentation in order to protect it from failure due to high temperatures.” The result is a stronger and sweeter alcohol, which can be enjoyed cloudy like tak-ju or can also be clarified and drunk as a clear cheong-ju, Mellor explains.

It’s also a relatively rare expression of sool to keep your eyes peeled for while in Korea. “This category was all but lost in the modern sool industry, and even today there are very few producers of gwaha-ju due to the aging time, effort and cost to produce. However, it is one of the most richly flavoured and aromatic sool experiences to be had, and if you find yourself in Korea, don’t miss it!”

Sogok-ju

According to Wessa, there are 62 breweries still operating in Korea, all of them being 500 years old and still producing sogok-ju house to house: “There are quite intense rivalries between families,” Wessa recounts. Rice, water and nuruk constitute this traditional drink, but other ingredients like ginger. chili peppers, and angelica roots can also be added. “Every sogok-ju is a signature product for each brewer. In terms of minerals and umami, which are key aspects of sools, this is one of the most perfect expressions.”

Sungnyung

This non-alcoholic drink closes our list, and it’s an interesting one in terms of traditions and renewed popularity. With its first known trace being found before 1400, sungnyung has kept its original, homemade nature intact: it is made by pouring warm water onto the layer of grains that sticks to the bottom of a pan after cooking rice. The infusion gathers the rice flavour, and is then served as an after-meal drink, to aid digestion.