Jim Meehan: When it comes to bar design, we all have the power to work with it

The author of ‘The PDT Cocktail Book’ and ‘Meehan’s Bartender Manual’ knows we can’t always choose our dream bar design. But we can work with it. He explains how for owner, management and bartenders

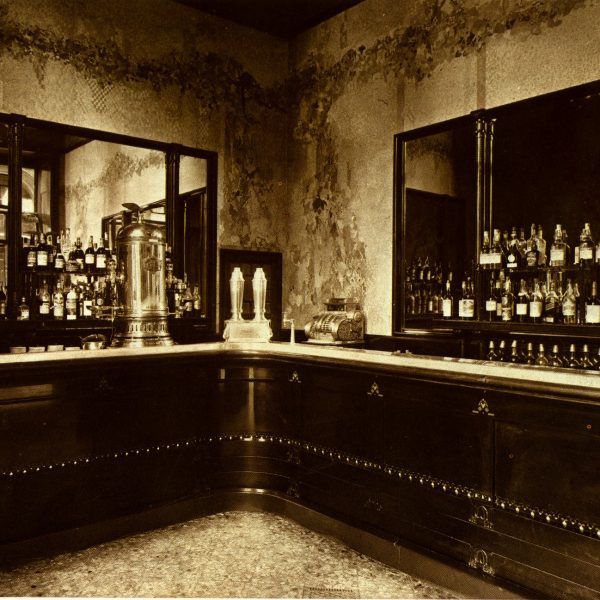

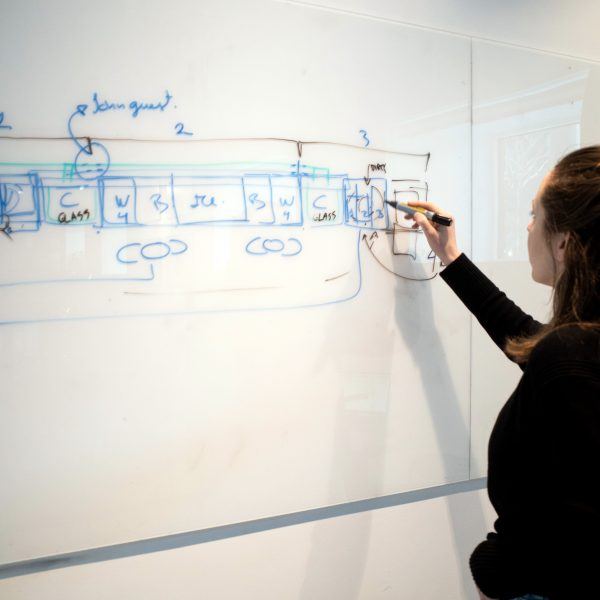

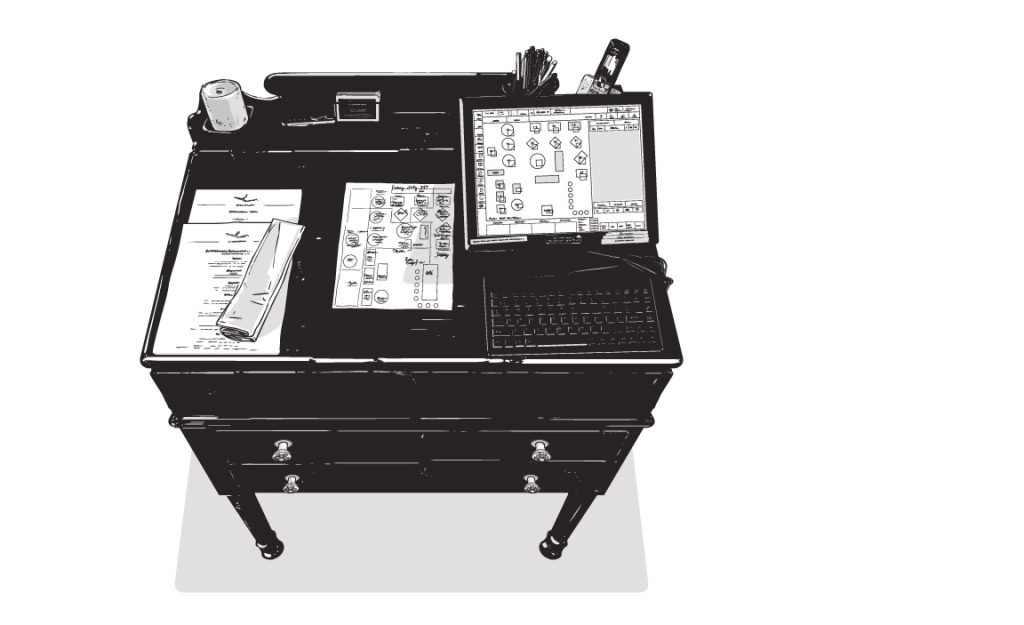

After 12 years working behind other operators’ bars – including Audrey Saunders’ Pegu Club and a little-known landmark in Madison, Wisconsin, Paul’s Club – I got my first opportunity to design my own work stations for PDT in 2007. I included renderings of it, along with the bar’s first and second level floorplans in The PDT Cocktail Book in 2011. I got so much positive feedback about this section that in 2017, I wrote a whole chapter on bar design in Meehan’s Bartender Manual.

Since most bartenders don’t design their own bars on an unlimited budget, I got to thinking about how they play a key role in bringing bar design to life.

I divided the chapter into sections on location, concept, branding, interior design and décor with five floorplans of bars that exemplified these concepts and a home bar I helped design. As I reflect upon the usefulness of this chapter, I must confess that the information I’ve included in my book is probably better suited to a well-funded operator about to embark upon an ambitious bar project with a kitchen designer, architect and experienced bar manager than most bartenders, who have to make do with someone else’s setup.

Since most bartenders don’t get to design their own bars on an unlimited budget, I got to thinking about how owners, operators and bartenders each play a key role in bringing bar design – whether your own, or someone else’s – to life. In this context, I’ve framed design as the plan you hand over to the builders (operators once a space is constructed).

While great design has the capability of making an object or place’s use more enjoyable and memorable, like driving a Ferrari or sitting in an Eames lounge chair, achieving its full potential requires skill and imagination by its users.

For owners

Undoubtedly, the easiest time and place to get bar design right is well before the business opens, when the owners take over a space, hire an architect, contractor and kitchen designer to build their dream venue. Inviting a bar manager with service experience into the initial meetings with the owners and builders, which almost always occur with the GM and chef, helps ensure that front-of-house needs, like shared walk-in refrigerator and dry storage space, are allocated equitably.

Major equipment and appliance purchases, along with the layout and orientation of where service hubs (like a host stand, bar, kitchen and manager’s office) will be only typically happen once; and that’s sometime between the owners taking the keys from the landlord and the business’s opening day.

The importance of these decisions cannot be overstated. Making them in meetings with the key stakeholders who will oversee operations is crucial so the space can be designed to facilitate its operator’s intentions. You tailor the suit to the person, not vice versa.

The cost of closing a busy or underachieving restaurant for multiple days after it opens to remodel it with improvements can be avoided if electricity and plumbing are installed during the buildout to not only achieve a business’s ambitions, but grow it.

This means investing in plumbing and electricity hook ups in spaces where costly machinery such as ice machines or refrigeration may be added later if the conservative estimate of a business’s potential is exceeded. Installation of new equipment and machinery can be completed over a short holiday weekend, or even at night: if permitted, messy construction and busy contractors can be avoided.

The key to designing a successful bar for operators is having the vision and experience to imagine it operating at full throttle.

The key to designing a successful bar for operators is having the vision and experience to imagine it operating at full throttle. If you design a bar to handily accommodate its staff when they’re stretched to accommodate their busiest service, you’ll set them up for success. This includes everything from amenities like a coat check near the door, to essentials, such as a short distance from the service bar to the tables.

The two areas of design that have changed the most since my book was released are adequate ventilation and outdoor seating options, which sure come in handy during a respiratory pandemic and will remain vital in the future.

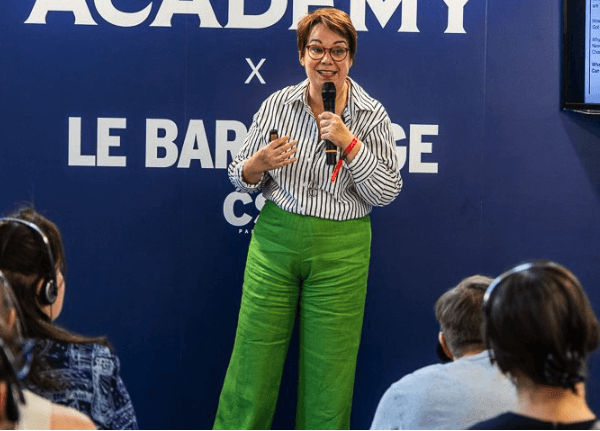

For management

My book is oriented towards design decisions for owners, but what about bar managers and beverage directors, who frequently get brought in after the chef has spent the lion share of the opening budget (right after the architect finished designing another bar with no space for garbage bins, recycling or adequate plumbing for sinks and installed a proper dishwasher)?

While it’s typically too late to rectify these oversights, management must still make the most of the bar design they inherit from the opening team.

The three key features (which are installed as part of the design) of a bar that every savvy operator adjusts throughout service are lighting, temperature and the volume/playlist of music. Surely, the owners installed lights on dimmers (hint hint, owners) and tested them over the course of a full day before opening so they could be programmed for the gradual changes in natural light from sunup to sundown?

And for hot or cold environs, the thermostat must be monitored to keep each HVAC zone of the room at the ideal temperature for harried servers and cooks and nattily dressed guests occupying the same space. Most crucially, the volume and type of music must be tinkered with to maintain the right energy.

There’s a whole chapter on the cocktail menu – because it’s that important – but from an operational standpoint, the menu is one of the most important design elements for a bar venue, as it’s the user’s manual customers rely on to construct their experience.

Guests are looking for clues when they consider what to order: merchandising should guide them to it instinctively.

From the staff’s perspective, a menu can break service by either being too broad and ambitious, causing too much churn, or too esoteric and mundane, yielding too little. Merchandising menu items through product placement and service rituals that call attention to what you want to sell (and are most capable and successful doing so) is good restaurant design. Guests are looking for clues when they consider what to order: merchandising should guide them to it instinctively.

One last design consideration for managers is customer flow and capacity. Do you seat the entire restaurant or bar all at once, or stagger reservations or walk-ins to allow orders to be placed and executed for an even service? Do you start a line when your bar is at capacity, tell people you’ll call them when there’s availability, or allow a bar to become overcrowded?

While packing a venue might seem like a good idea from financial perspective, there’s a sweet spot between a bar and kitchen achieving their potential (and growing from it) and utter chaos, which leads to disappointed customers and staff disaffection. This dynamic sweet spot is a design challenge on a nightly basis.

For staff

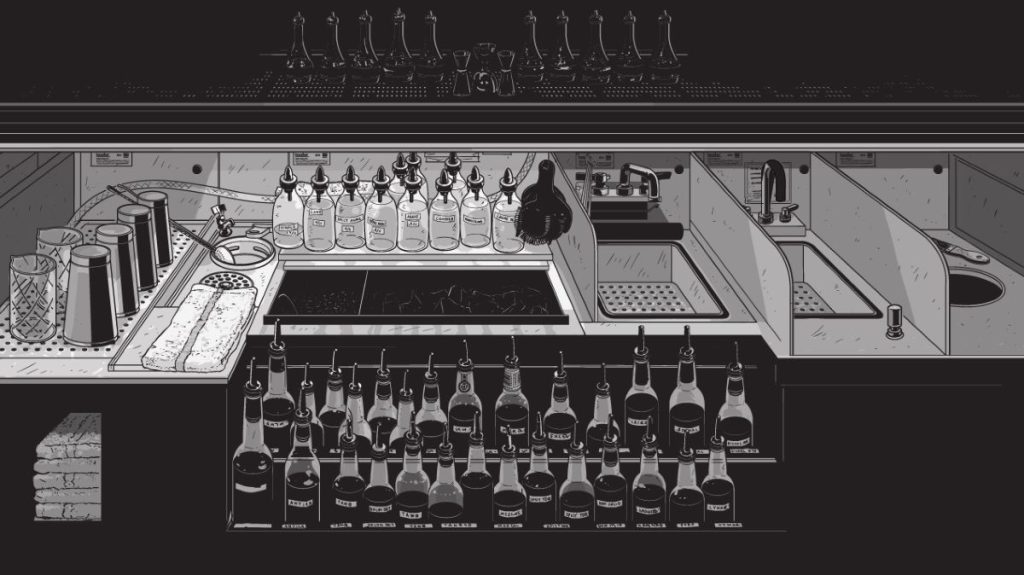

While it’s tempting for some bartenders to write off a bar for its poor design, the fact of the matter is that most bars aren’t well designed to begin with, or have major challenges due to unavoidable structural issues like supporting beams in an old building. Approaching each bar with the intention of making lemonade with its design lemons is how I’ve approached my career, with mise en place being the key tool to get the job done.

Mise en place, which is the configuration in which staff set up their station with tools, bottles, garnishes, menus, napkins, glassware, cutlery and other items for service is crucial for success. While most bars and restaurants will standardise their set ups as a point of service, there’s always room for customisation to improve everything, from the way towels and napkins are folded to where water pitchers are stored and refilled for easy access.

Creative mise en place shaves seconds off each move a server makes, which leads to time saving that can generate a whole extra turn of a dining room over the course of an evening.

The other essential and easy-to-overlook design element bartenders hold the power to unlock is service. Great service can make up for the most difunctionally designed bar or restaurant. Bartending is a (functional) show put on for the customers, and as the star of that production, a great bartender can hide a lot of questionable design decisions in the darkness around their spotlight if they keep their composure and expertly guide their guest through the experience they want their guests to have.

Great service can make up for the most difunctionally designed bar or restaurant.

One of my favorite quotes from my interviews for Meehan’s Bartender Manual is from Jack McGarry, who told me that: “As soon as I walk into a bar I can feel whether there’s negativity. Obviously, the first thing is, is this bar good? Do the operators care about it? But from there, you also sense the operator’s attitude. Are they an optimistic or positive person? You’ll quickly see that trait mirrored in their staff.”

I couldn’t agree more: positivity in the form of a sense of hopeful possibility is what each and every guest is looking for when they sit down in front of your bar. Knowing this, and preparing yourself mentally, physically and emotionally each day before you open the doors is the operational equivalent of putting gas in a car or plugging in the fridge.

Design must be animated in this way, as a well-designed bar should function intuitively, but the imagination and heart to make the most of it must come from its users.