Extracting flavour series: Why infusion doesn’t need to be complicated

In the first a new series on extracting flavour, Monica Berg shares her insights into the technique of infusion and why keeping it simple can get you the best results

In this series which will span over several weeks, we’ll look at some of the most common ways to extract flavour from an ingredient – and some less common – all with the aim of making delicious drinks.

Let’s start with one of the most frequently used methods – infusion.

But before we start, let’s get the technicalities out of the way: infusion, maceration, decoction – when talking about these in culinary terms but with creating drinks as the goal, they are in (almost) every practical sense, the same. Yes, there are minor variances and nuances, but to keep this easy and understandable, let’s agree to call them all ‘infusions’. At least, for now.

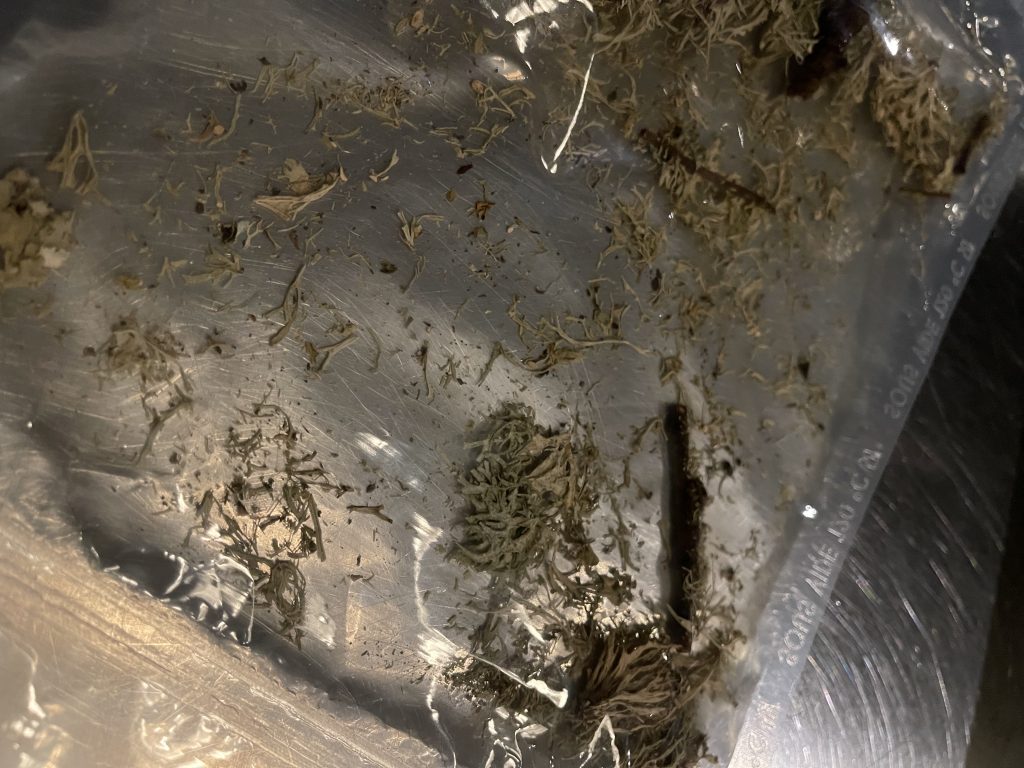

The main purpose of infusions (meaning to steep or soak something, whether it is a herb, a fruit or a botanical, in a liquid) is to extract flavour. It is often the first advanced technique many of us encounter when we start our bartender journeys, but keeping it simple is far from being stupid. As someone who worked in the midst of the anything-goes, infused-Martini craze (passionfruit, green apple or rhubarb Martinis were definitely the biggest hitters back in my club days) the method was pretty straight-forward: infuse whatever ingredient you wanted into vodka, then mix with liqueur, fruit juice and (maybe) some citrus, shake and voila.

Since then, obviously, I’ve learned a lot more when it comes to technique; about layering flavour and being more purposeful in the way I extract flavours – but what remains the same is that this is still one of my favourite ways to capture the true nature of any ingredient.

So let me take you through my thinkings and tinkerings on the topic of infusions – which, I might add, are only my personal opinions, and will be quite different from many others.

The three Ts

When tackling infusions, there are three things you simply cannot ignore: time, texture and temperature. These three elements will deeply impact your end result and, more often than not, you need to utilise or conquer all three (often together) to get the best result.

Let’s start with time. We often say that time is a luxury, and I think this is very true when it comes to prep – and sometimes if you have a prep that’s not going in the direction you want, the best thing to do is to leave it and see how it develops. My shortest infusions often last no longer than a few hours (when using ingredients like coffee beans or other very potent ingredients) whilst other times I can leave ingredients to infuse for months or even years.

If you want to infuse strawberries into something, time will be important because how long you infuse something will impact how much flavour you get. However, this can be manipulated if you change the ratio between strawberries and liquid by adding more strawberries to shorten the time needed to infuse. Looking at the reverse, if you have less strawberries to liquid, then the time you infuse needs to be longer to get a similar result.

You can also influence the process by maximising the surface ratio. For example, by cutting the strawberries into smaller pieces you get more surface area, or you can put everything into a blender and puree it, which will create maximum integration between the two ingredients, but will add to the prep time as you now need to strain it back to a clear liquid (the harsh treatment in the process can also lose you some of the more volatile aromatics of the strawberry).

Now, moving on to texture. Alcohol and fat are both excellent carriers of flavour, and when you understand how they work, it makes it easier to let them do the hard work for you. If, for example, you infuse strawberries into milk versus heavy cream, the end result will be different because the texture of the liquid will react differently to the strawberry and carry over different elements. Similarly, you can say this is the case when we infuse strawberries into alcoholic liquids, as the ABV will not only impact the texture of the liquid but, more importantly, effect how much water is present in the liquid, and different strengths will impact what flavours gets extracted in the process.

If you imagine the fresh strawberry on its own as a 360-degree picture of the flavour profile you want to capture, then all these infusions and preparations we do are different angles or isolated parts of that picture – and to get the full image, we need to puzzle them back together. This, in a way, is how I look at an ingredient when I taste it and deconstruct it in my mind in order to know what techniques to use to reassemble it back together into a finished cocktail.

In practical terms, this means that if you do a strawberry infusion in vodka, gin or any other high(er)-ABV product, you will get a one-dimensional picture of what a strawberry looks like; but if you were to also do an infusion in a lower-ABV liquid like vermouth or fortified wine, and then combine the two together in your drink, your strawberry universe will start to look a little bit more real and complex.

Lastly, you have temperature. This is perhaps the most controversial of the three for me. As I mentioned before, I use infusions mostly to help capture what the true essence of an ingredient is, and this means I’m always chasing those delicate nuances.

If you’ve ever bitten into a perfect summer strawberry, it starts off with that juicy brightness, followed by the mellow fruity sweetness that lingers almost until the end, before it finishes with a tiny, almost unnoticeable, hit of acidity. What it doesn’t mean is the jammy, almost candy-like flavours you often get when you add heat to it – which is why I never do.

Obviously, there are no rules without exceptions, and I do add heat when working with dried ingredients, or ingredients such as spices and seeds where you want to access the essential oils, etc – but, more often than not, I work in what you so often unscientifically call ‘room temperature’. When working with fresh fruits or vegetables at their natural, seasonal peak, I never use heat. If the fruit is very bruised or damaged, I’d argue that using it for infusion might not be the way to go – fermentation could be a better option.

Simplicity conquers all

I’m always an advocate for less AND more, meaning less technique applied, but more focus on the raw material, because by working with the best ingredients you don’t have to do much to make it taste delicious.

In the end, there are many techniques you can choose to use when infusing: traditional steeping with or without heat, rapid infusion using iSi, vacuum sealed, sous vide or supersonic – they all have pros and cons. But I think the biggest question is the cost. For example, some say it’s timesaving and efficient to use the iSi chargers to rapidly infuse a liquid by using pressure, but in the bigger picture, you’ll need to factor the cost of those cartridges into the final drink, which can make it quite expensive and wasteful. Likewise with equipment like a vacuum sealer or a supersonic, the initial cost for the machine is quite high and it takes up a lot (!) of space, so you’ll need to factor in how many drinks you’ll need to make to justify the investment.

Infusions, when used cleverly, can really help you diversify your drinks, and just because it’s seemingly simple, don’t let anyone fool you into thinking it’s easy. Used correctly it will outshine all the more ‘advanced’ techniques, any day.